The Existential Cost of Hsieh’s Hourly Performance

Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performances represents one of the most ambitious and uncompromising explorations of time, endurance, and artistic commitment in late 20th-century art. Born in Taiwan and later emigrating to the United States, Hsieh staged five consecutive year-long performances between 1978 and 1986, each imposing intense physical and psychological demands on his daily life. The series, defined by constraints on confinement, exposure, discipline, and presence, pushed the boundaries of what a “performance” can be. While each work stands as a singular statement, together they form a sustained inquiry into how human experience is shaped by time and by the restrictions—self-imposed or societal—that govern our actions.

His first year-long work (1978–1979), the Cage Piece, confined him to a small cell without any form of entertainment or communication. The second, known as the Time Clock Piece (1980–1981), required him to punch a time clock every hour on the hour, sacrificing continuous sleep. In the third piece, Outdoor Piece (1981–1982), he lived completely outdoors, never entering a building or vehicle. For the fourth, Rope Piece (1983–1984), Hsieh and Linda Montano were tied together by an eight-foot rope but never touched throughout the year. Finally, in the No Art Piece (1985–1986), Hsieh avoided any engagement with art—creating, discussing, or even viewing it—suspending his artistic practice entirely.

The conception of the Time Clock Piece grew out of Hsieh’s longstanding fascination with how time and routine shape human experience—a theme he first probed in his Cage Piece. Having immigrated to the United States from Taiwan in the mid-1970s, he was acutely aware of both the precarity of labor and the literal clocking-in that underpins daily working life. Seeking a more direct confrontation with the structures of time discipline, he devised a piece that would treat each hour of the day as a mandatory checkpoint, turning a simple, mechanically administered act into the central ritual of an entire year. Conceptually, he was drawn to the uniformity and objectivity of the punch clock—commonly used in factories and other work settings—because it functioned as an impartial witness to his relentless schedule. In doing so, he magnified the alienating effect of dividing human existence into discrete labor units.

At this moment in art history, performance was moving from the fringes of conceptual practice to a more visible—though still challenging—position in the broader cultural scene. Influential figures like Chris Burden, Vito Acconci, and Marina Abramović had garnered attention for pushing physical and psychological boundaries, while conceptualists focused on ideas and process rather than traditional objects. Arriving in New York in the late 1970s, Hsieh found a setting that valued experimentation, yet his intense focus on durational extremes and rigorous self-imposed constraints set his work apart. By engaging the tools of labor discipline and turning them into a source of artistic inquiry, he connected his project to a contemporary discourse about the role of time, labor, and documentation in artistic practice.

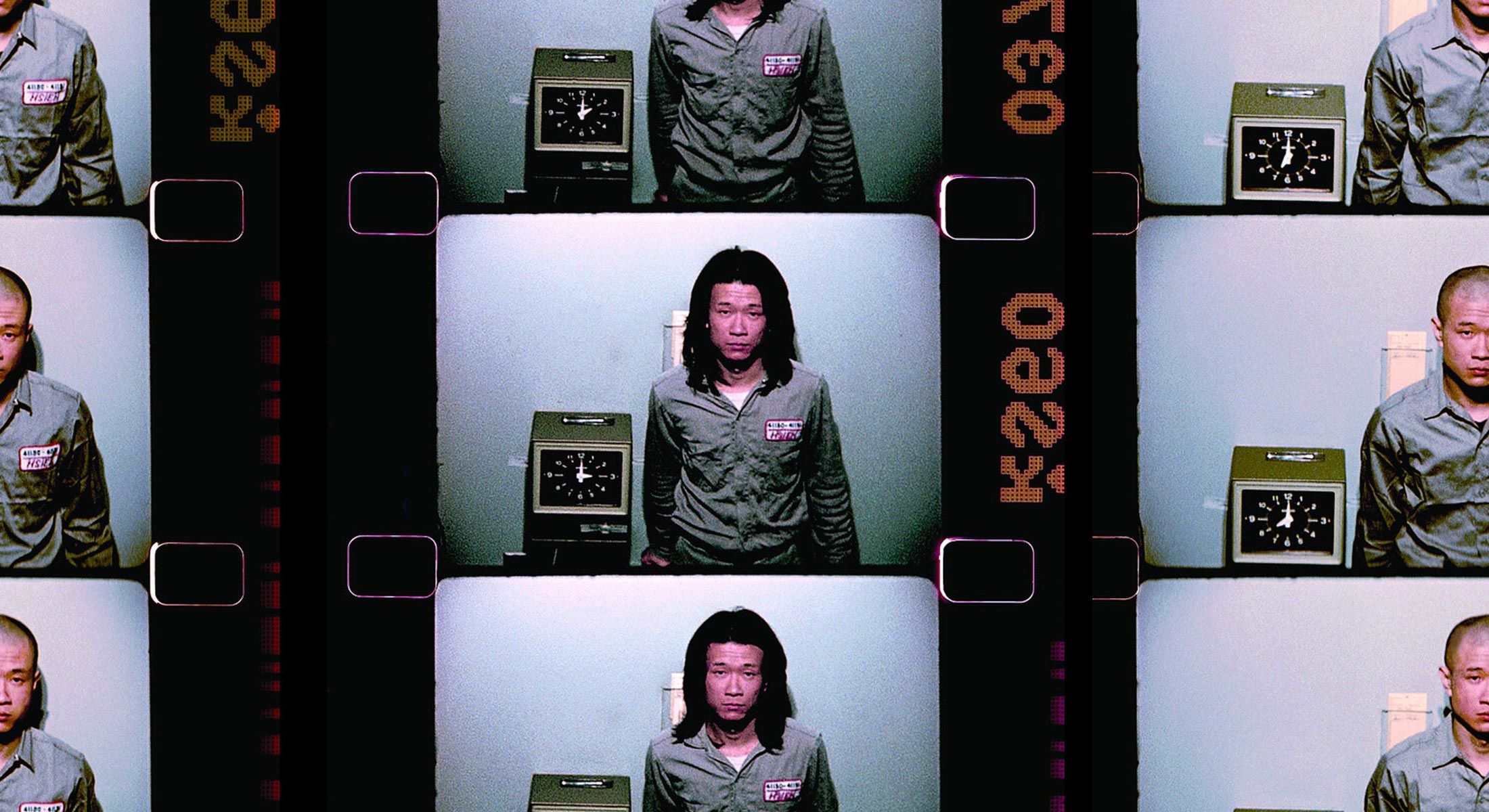

The piece took place primarily in Hsieh’s New York studio, where he installed a standard time clock and set up a backdrop for taking instant photographs each time he punched in. Before the official start on April 11, 1980, he shaved his head so its regrowth would serve as a visual calendar. He established strict rules: once every hour, on the hour, he had to pull the card from the rack, punch the clock, and snap a photograph of himself—no exceptions. This requirement meant he could never sleep more than 50 or so minutes at a stretch, could not travel far from the studio, and was perpetually tethered to an unyielding temporal schedule. Each day’s punch cards became a physical record, while the hundreds of instant snapshots formed a kind of stop-motion diary of his changing appearance and mental state. By devoting a year of his life to this meticulous process, Hsieh transformed a routine labor practice into an extreme artistic statement about discipline, time, and the profound ways our lives are shaped by the smallest, most repetitive tasks.

By the time the Time Clock Piece concluded on April 11, 1981, he had punched the time clock roughly 8,600 times (missing only a small percentage of the hourly alarms). The final punch—like the first—took place in his New York studio, marking an official close to twelve months of relentless, regimented self-surveillance. In a brief statement summarizing his experience, Hsieh commented on how the piece exposed the arbitrary nature of time discipline, saying, “When you cut your life into hourly segments, you feel that living itself is labor.” This blunt reflection underscored his sense that the entire year had become a form of unpaid work—an inversion of everyday wage labor that used the clock’s authority to highlight its own absurdity.

Reception within the art world was both astonished and admiring. Critics regarded the performance as a radical extension of Conceptual Art’s fascination with duration and documentation. The Village Voice ran an article shortly afterward, describing it as “the purest form of clock-punching imaginable” and likening it to a “minimalist sculpture” in which time was the material. Fellow performance artist Linda Montano, who later collaborated with Hsieh on his 1983–1984 Rope Piece, noted that the Time Clock Piece displayed “a level of discipline that made most of us question our own relationship to structure, sleep, and freedom.” Although Hsieh did not dwell on emotional impressions, he acknowledged that living by the clock had been “the hardest kind of meditation,” as he put it in a post-performance conversation with friends. Some questioned the toll on his health, to which he replied simply: “I survived.”

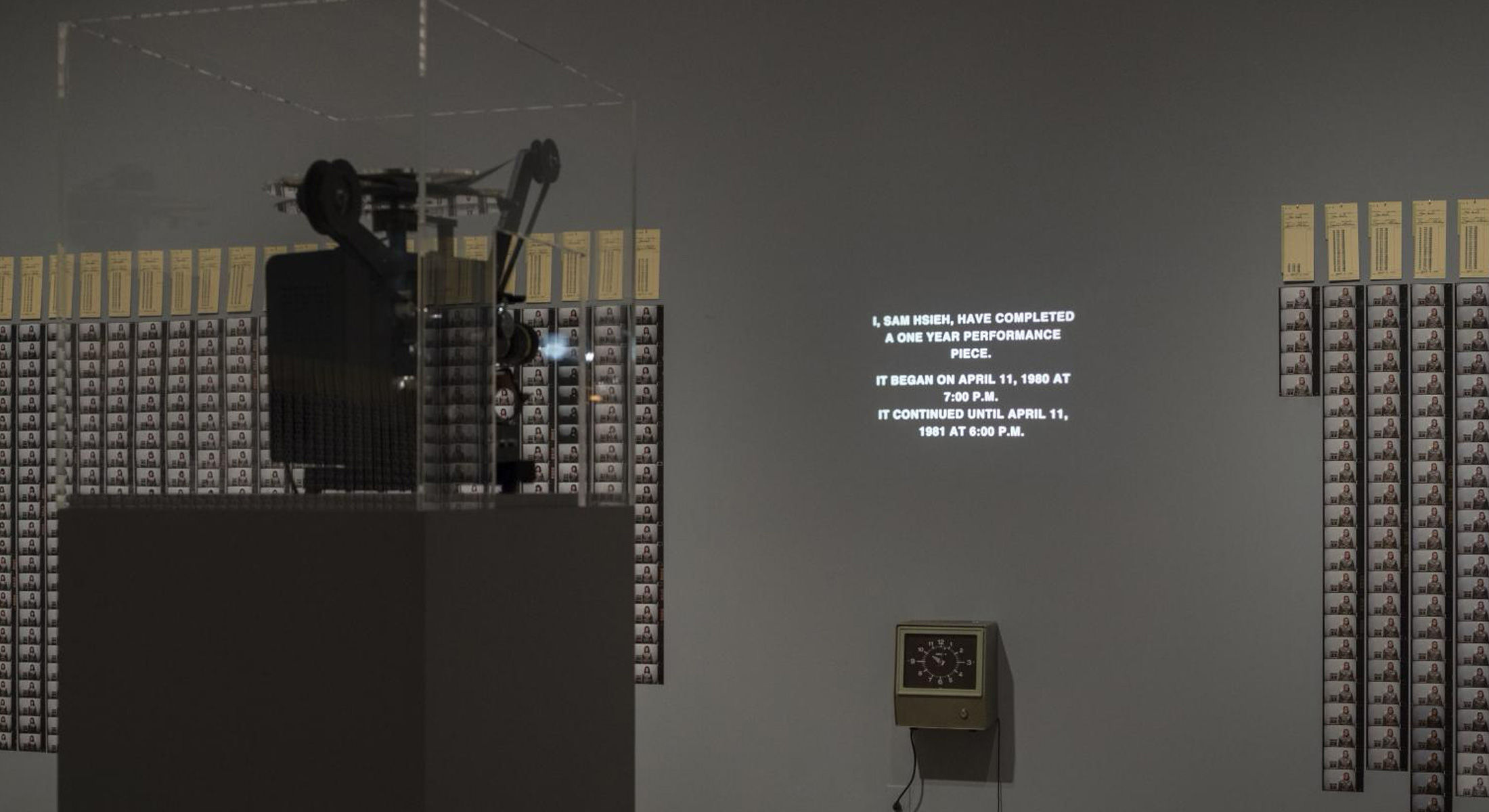

Shortly after the conclusion, Hsieh exhibited the full documentation—which included the thousands of punch cards and the rapid-fire time-lapse photographs—in a modestly attended but deeply impactful presentation. Seeing all the data at once was, for many viewers, a shock: the accumulation of images and laborious records revealed just how thoroughly every hour of his life had been conscripted into art. This body of evidence was held up as proof of his unwavering dedication and, in time, became influential in shaping debates on what performance art could encompass. Although he refrained from sentimental or heroic language, he consistently pointed to the quiet profundity of the ritual, often describing the Time Clock Piece as an “experiment with life itself.” Critics widely agreed that the stark combination of industrial repetition and personal vulnerability made it one of the most seminal examples of durational performance in modern art.

The Time Clock Piece remains, above all, a stark reminder of the absolute authority time holds over human life. In chronicling Hsieh’s unwavering devotion to a machine-bound schedule, it lays bare the cost of treating our very existence as an unending task. Rarely has art so completely relinquished the promise of transcendence in favor of a dogged, daily ritual that feels both industrial and monastic. The result is a disturbing beauty—an unremitting record of our vulnerability to the clock and, by extension, to mortality itself. This performance does not just sit among the landmarks of conceptual and endurance art; it stands as a precise and unflinching confrontation with life’s ultimate currency, daring us to examine how we spend each hour allotted to us. If one measure of great art is its capacity to cast the everyday in a new light, then the Time Clock Piece has rightfully secured its place in history by converting an ordinary punch card into an existential mirror.

His first year-long work (1978–1979), the Cage Piece, confined him to a small cell without any form of entertainment or communication. The second, known as the Time Clock Piece (1980–1981), required him to punch a time clock every hour on the hour, sacrificing continuous sleep. In the third piece, Outdoor Piece (1981–1982), he lived completely outdoors, never entering a building or vehicle. For the fourth, Rope Piece (1983–1984), Hsieh and Linda Montano were tied together by an eight-foot rope but never touched throughout the year. Finally, in the No Art Piece (1985–1986), Hsieh avoided any engagement with art—creating, discussing, or even viewing it—suspending his artistic practice entirely.

The conception of the Time Clock Piece grew out of Hsieh’s longstanding fascination with how time and routine shape human experience—a theme he first probed in his Cage Piece. Having immigrated to the United States from Taiwan in the mid-1970s, he was acutely aware of both the precarity of labor and the literal clocking-in that underpins daily working life. Seeking a more direct confrontation with the structures of time discipline, he devised a piece that would treat each hour of the day as a mandatory checkpoint, turning a simple, mechanically administered act into the central ritual of an entire year. Conceptually, he was drawn to the uniformity and objectivity of the punch clock—commonly used in factories and other work settings—because it functioned as an impartial witness to his relentless schedule. In doing so, he magnified the alienating effect of dividing human existence into discrete labor units.

At this moment in art history, performance was moving from the fringes of conceptual practice to a more visible—though still challenging—position in the broader cultural scene. Influential figures like Chris Burden, Vito Acconci, and Marina Abramović had garnered attention for pushing physical and psychological boundaries, while conceptualists focused on ideas and process rather than traditional objects. Arriving in New York in the late 1970s, Hsieh found a setting that valued experimentation, yet his intense focus on durational extremes and rigorous self-imposed constraints set his work apart. By engaging the tools of labor discipline and turning them into a source of artistic inquiry, he connected his project to a contemporary discourse about the role of time, labor, and documentation in artistic practice.

The piece took place primarily in Hsieh’s New York studio, where he installed a standard time clock and set up a backdrop for taking instant photographs each time he punched in. Before the official start on April 11, 1980, he shaved his head so its regrowth would serve as a visual calendar. He established strict rules: once every hour, on the hour, he had to pull the card from the rack, punch the clock, and snap a photograph of himself—no exceptions. This requirement meant he could never sleep more than 50 or so minutes at a stretch, could not travel far from the studio, and was perpetually tethered to an unyielding temporal schedule. Each day’s punch cards became a physical record, while the hundreds of instant snapshots formed a kind of stop-motion diary of his changing appearance and mental state. By devoting a year of his life to this meticulous process, Hsieh transformed a routine labor practice into an extreme artistic statement about discipline, time, and the profound ways our lives are shaped by the smallest, most repetitive tasks.

By the time the Time Clock Piece concluded on April 11, 1981, he had punched the time clock roughly 8,600 times (missing only a small percentage of the hourly alarms). The final punch—like the first—took place in his New York studio, marking an official close to twelve months of relentless, regimented self-surveillance. In a brief statement summarizing his experience, Hsieh commented on how the piece exposed the arbitrary nature of time discipline, saying, “When you cut your life into hourly segments, you feel that living itself is labor.” This blunt reflection underscored his sense that the entire year had become a form of unpaid work—an inversion of everyday wage labor that used the clock’s authority to highlight its own absurdity.

Reception within the art world was both astonished and admiring. Critics regarded the performance as a radical extension of Conceptual Art’s fascination with duration and documentation. The Village Voice ran an article shortly afterward, describing it as “the purest form of clock-punching imaginable” and likening it to a “minimalist sculpture” in which time was the material. Fellow performance artist Linda Montano, who later collaborated with Hsieh on his 1983–1984 Rope Piece, noted that the Time Clock Piece displayed “a level of discipline that made most of us question our own relationship to structure, sleep, and freedom.” Although Hsieh did not dwell on emotional impressions, he acknowledged that living by the clock had been “the hardest kind of meditation,” as he put it in a post-performance conversation with friends. Some questioned the toll on his health, to which he replied simply: “I survived.”

Shortly after the conclusion, Hsieh exhibited the full documentation—which included the thousands of punch cards and the rapid-fire time-lapse photographs—in a modestly attended but deeply impactful presentation. Seeing all the data at once was, for many viewers, a shock: the accumulation of images and laborious records revealed just how thoroughly every hour of his life had been conscripted into art. This body of evidence was held up as proof of his unwavering dedication and, in time, became influential in shaping debates on what performance art could encompass. Although he refrained from sentimental or heroic language, he consistently pointed to the quiet profundity of the ritual, often describing the Time Clock Piece as an “experiment with life itself.” Critics widely agreed that the stark combination of industrial repetition and personal vulnerability made it one of the most seminal examples of durational performance in modern art.

The Time Clock Piece remains, above all, a stark reminder of the absolute authority time holds over human life. In chronicling Hsieh’s unwavering devotion to a machine-bound schedule, it lays bare the cost of treating our very existence as an unending task. Rarely has art so completely relinquished the promise of transcendence in favor of a dogged, daily ritual that feels both industrial and monastic. The result is a disturbing beauty—an unremitting record of our vulnerability to the clock and, by extension, to mortality itself. This performance does not just sit among the landmarks of conceptual and endurance art; it stands as a precise and unflinching confrontation with life’s ultimate currency, daring us to examine how we spend each hour allotted to us. If one measure of great art is its capacity to cast the everyday in a new light, then the Time Clock Piece has rightfully secured its place in history by converting an ordinary punch card into an existential mirror.

Join the Club

Follow the organizations you care about. Track and save events as they’re announced, and discover your next enriching experience on Ode.